|

Civil War Battles |

|

State War Records |

| AL - AK - AZ - AR - CA - CO - CT - DE - FL - GA - HI - ID - IL - IN - IA - KS - KY - LA - MA - MD - ME - MI - MN - MS - MO - MT - NE - NV - NH - NJ - NM - NY - NC - ND - OH - OK - OR - PA - RI - SC - SD - TN - TX - UT - VT - VA - WA - WV - WI - WY |

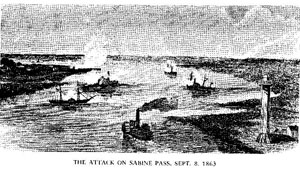

The Battle of Sabine Pass (Second)

September 8, 1863 in City/County, Texas

|

|||||||||||||||||

|

The battle of Sabine Pass, on September 8, 1863, turned back one of several Union attempts to invade and occupy part of Texas during the Civil War.

The United States Navy blockaded the Texas coast beginning in the summer of 1861, while Confederates fortified the major ports. Union interest in Texas and other parts of the Confederacy west of the Mississippi River resulted primarily from the need for cotton by northern textile mills and concern about French intervention in the Mexican civil war.

In September 1863 Gen. Nathaniel P. Banks sent by transport from New Orleans 4,000 soldiers under the command of Gen. William B. Franklin to gain a foothold at Sabine Pass, where the Sabine River flows into the Gulf of Mexico. A railroad ran from that area to Houston and opened the way into the interior of the state. The Western Gulf Blockading Squadron of the United States Navy sent four gunboats mounting eighteen guns to protect the landing.

At Sabine Pass the Confederates recently had constructed Fort Griffin, an earthwork that mounted six cannon, two twenty-four pounders and four thirty-two pounders. The Davis Guards, Company F of the First Texas Heavy Artillery Regiment, led by Capt. Frederick Odlum, had placed stakes along both channels through the pass to mark distances as they sharpened their accuracy in early September. The Union forces lost any chance of surprising the garrison when a blockader missed its arranged meeting with the ships from New Orleans on the evening of September 6. The navy commander, Lt. Frederick Crocker, then formed a plan for the gunboats to enter the pass and silence the fort so the troops could land. The Clifton shelled the fort from long range between 6:30 and 7:30 A.M.

On the 8th, while the Confederates remained under cover because the ship remained out of reach for their cannon. Behind the fort Odlum and other Confederate officers gathered reinforcements, although their limited numbers would make resistance difficult if the federal troops landed.

Finally at 3:40 P.M. the Union gunboats began their advance through the pass, firing on the fort as they steamed forward. Under the direction of Lt. Richard W. Dowling the Confederate cannoneers emerged to man their guns as the ships came within 1,200 yards. One cannon in the fort ran off its platform after an early shot. But the artillerymen fired the remaining five cannon with great accuracy. A shot from the third or fourth round hit the boiler of the Sachem, which exploded, killing and wounding many of the crew and leaving the gunboat without power in the channel near the Louisiana shore. The following ship, the Arizona, backed up because it could not pass the Sachem and withdrew from the action. The Clifton, which also carried several sharpshooters, pressed on up the channel near the Texas shore until a shot from the fort cut away its tiller rope as the range closed to a quarter of a mile.

That left the gunboat without the ability to steer and caused it to run aground, where its crew continued to exchange fire with the Confederate gunners. Another well-aimed projectile into the boiler of the Clifton sent steam and smoke through the vessel and forced the sailors to abandon ship. The Granite City also turned back rather than face the accurate artillery of the fort, thus ending the federal assault. The Davis Guards had fired their cannon 107 times in thirty-five minutes of action, a rate of less than two minutes per shot, which ranked as far more rapid than the standard for heavy artillery. The Confederates captured 300 Union prisoners and two gunboats. Franklin and the army force turned back to New Orleans, although Union troops occupied the Texas coast from Brownsville to Matagorda Bay later that fall. The Davis Guards, who suffered no casualties during the battle, received the thanks of the Confederate Congress for their victory. Careful fortification, range marking, and artillery practice had produced a successful defense of Sabine Pass.

The Battle of Sabine Pass was of little tactical or strategic significance. A Confederate supply line from Mexico to Texas was never established, and in any case it could not have effectively supplied the states east of the Mississippi once the Union controlled the whole of that river after its victory at Vicksburg in July.

The Confederacy was therefore forced to continue its reliance on blockade running to import valuable materiel and resources.